Photos: Life along a ‘dead’ river in Bangladesh.

The devastation of areas like the Buriganga comes into greater focus in the run-up to Earth Day, when people worldwide mobilise in support of protecting the environment. White foam is formed in the water as ferryman Abdul Karim, 72, rides his boat in the Buriganga river near the Sadarghat area in Dhaka. [Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters] Two decades ago, Nurul Islam, 70, earned his living by fishing in the Buriganga river that flows southwest of the Bangladesh capital of Dhaka and was once its lifeline. Now, with hardly any fish to be found in the “dead” river, thanks to pollution from the widespread dumping of industrial and human waste, Islam sells street food on a small cart nearby to make ends meet. “Twenty years ago this river water was good. It was full of life,” said Islam, whose family has been living on the bank of the river for generations. “We used to bathe in the river. There were lots of fish … many of us used to earn a living by catching fish in the river. Now the scenario has changed.” The Buriganga, or the “Old Ganges”, is so polluted that its water appears pitch black – except during the monsoon months – and emits a foul stench throughout the year. The South Asian nation of nearly 170 million, with about 23 million living in Dhaka, has about 220 small and large rivers, and a large chunk of its population depends on rivers for livelihoods and transport. The devastation of areas like Buriganga comes into greater focus in the run-up to Earth Day, when people worldwide celebrate and mobilise in support of protecting the environment. Bangladesh is the world’s second-biggest garment exporter after China, but citizens and environmental activists say the booming industry is also a major contributor to the ecological decline of the river. Untreated sewage, by-products of fabric dyeing and other chemical waste from nearby mills and factories flow in daily. Polythene and plastic waste piled on the riverbed have made it shallow and caused a shift in course. “Those who bathe in this river often suffer from scabies on their skin,” said Siddique Hawlader, 45, a ferryman who lives on his boat on the river. “Sometimes our eyes itch and burn,” he added. In 1995, Bangladesh made it compulsory for all industrial units to use effluent treatment plants to keep pollution out of its rivers, but industries often flout the rule. While the government makes regular checks to ensure the rules are being followed, it lacks the staff for “round-the-clock” monitoring, said environment official Mohammad Masud Hasan Patwari. The Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) said all textile factories had effluent treatment plants for wastewater. “This is mandatory and there is no way to skip the rules as they must ensure compliance with international standards,” said Shahidullah Azim, one of its officials. Pollution in the river water during the dry season was well above standard levels, a recent survey by the River and Delta Research Centre showed, identifying industrial sewage as the main culprit. “The once-fresh and mighty river Buriganga is now on the verge of dying because of the rampant dumping of industrial and human waste,” said Sharif Jamil of environment group the Bangladesh Poribesh Andolon. “There is no fish or aquatic life in this river during the dry season. We call it biologically dead.”

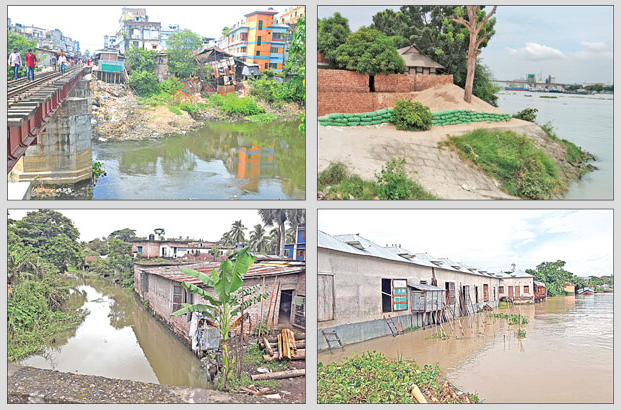

Over 500 rivers on verge of extinction

Grabbers continue to feast on rivers across the country, leading to the death of over 500 rivers. In the photos (from left), structures are seen constructed on the banks of the Karatoa River in Bogura and a river in Munshiganj (Up), Baleshwar River in Bagerhat and Palardi River in Barishal (Down). The photos were taken recently. — Photo: Collected As urban sprawl and industrialisation threaten arable lands across the country, a dark shadow looms over the survival of over 500 rivers due to rampant grabbing. Indiscriminate grabbing of rivers, khals, and other water bodies has resulted in a startling loss of natural resources, exacerbating frequent flooding and alarming environmental degradation. Despite a strong slogan “NodiBachleDeshBachbe (If rivers are alive, the country will be alive)” presented by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in 2019, efforts to protect these rivers have floundered. Mohammad Ezaz, Chairman of the River and Delta Research Centre (RDRC), stated, “A post-liberation survey found the existence of 1,274 rivers in the country. However, last month’s report from the National River Conservation Commission (NRCC) showed just 907. That means 367 rivers have been grabbed and are now nonexistent.” The encroachment epidemic is not confined to any one region. In Sirajganj, influential local figures, including ruling party leaders, have grabbed both banks of the Garadaho river for commercial purposes. AtaurRahman, a Thai glass trader, admitted to renting a shop along the bank for Tk 8,500 per month. In Gournadi in Barishal, the banks of the Palardi river have been usurped, with hundreds of shops and commercial establishments now standing where the river once flowed. Despite a list of 57,000 individuals and organisations implicated in river grabbing being released by the NRCC in 2018, the problem has escalated. According to Ezaz, “Incidences of encroachment on rivers have increased, necessitating an updated list of grabbers.” When questioned about the leasing of the Garadaho river bank, Mahbubur Rahman, executive engineer of the Water Development Board, acknowledged ignorance and assured that appropriate steps would be taken after an investigation into the grabbing. The unabated encroachment has resulted in a significant hike in land prices, further complicating the crisis. With arable lands shrinking due to the growing population and industrialisation, rivers have become the latest casualty in a long list of environmental concerns. While the government’s 2019 initiative aimed at safeguarding rivers has lost momentum, the escalating crisis makes it abundantly clear that immediate and decisive action is required. As rivers stand on the brink of extinction, this situation is more than an environmental disaster; it is a ticking time bomb with vast economic, social, and ecological implications. The voice of Mohammad Ezaz resonates more than ever: immediate action is necessary. The life of the rivers is, after all, intrinsically tied to the life of the country. If the rivers die, what becomes of the nation? New revelations indicate that influential politicians and businessmen are among those actively participating in river grabbing. For example, Zakir Hossain Sharif, President of the municipality Jubo League, owns ‘Sharif Sawmill’ at the Tarkir Char point of the river. When contacted, both Sharif and Shah Alam, former Ward BNP vice-president and owner of ‘Khan Sawmill’, claimed they had purchased the lands legally. Meanwhile, FarhadHossainMunshi, the son of Dal Mill owner KhalekMunshi, admitted that a portion of their mill land does indeed belong to the river. Such blatant disregard for the law doesn’t stop here. The Khakdon river in Barguna has suffered a similar fate. Instead of taking action, the Assistant Commissioner (Land) has allegedly leased out the river banks to the encroachers. The Bishkhali river in Patharghata and Bamnaupazilas has been converted into brickfields, further exacerbating the environmental crisis. Between February 2019 and June 2021, a total of 2,475 illegal structures were removed from the banks of the Shitalakhya river. However, the drive came to a halt due to the absence of a Magistrate. With the appointment of a new Magistrate in March 2023, over 700 establishments have been evicted, though the problem persists owing to irregular drives. Similarly, in Bogura, residential and commercial establishments litter the banks of the Korotoa river. Despite the ongoing construction of high-rise buildings at 28 different spots, local administration remains conspicuously silent. Bogura Deputy Commissioner Saiful Islam said, “The district administration has prepared a list of grabbers to take necessary action.” In Munshiganj, the price of land has surged due to infrastructural projects like the Padma Bridge, Dhaka-Mawa expressway, and Dhaka-Chattogram highway, making rivers like the Padma, Meghna, and Dhaleswari prime targets for encroachers. Dhaleswari’s banks are now riddled with mills and industries. National River Conservation Commission (NRCC) emphasised the dire need to protect rivers and restore their navigability to bolster the agro-based rural economy. Chairman Manjur Ahmed Chowdhury lamented the continuous encroachment due to “unseen power of the grabbers, insincerity of some officials, and attacks on eviction teams.” Chowdhury also highlighted that some government organisations are complicit in river grabbing, and the NRCC lacks the authority to take action against them.

Eviction Driver around rivers are not sustainable

Encroachment on river land has been an eternal problem in Bangladesh and the eviction drives that seek to put a stop to it seems unsustainable. Government authorities are saying that they are carrying out eviction drives against encroachment but the drives show an obvious bias towards individual encroachers. The drives carried out by the Bangladesh Inland Water Transport Authority (BIWTA) to evict illegal structures is a positive approach for sure and worth appraising, but the actions taken by the BIWTA so far have been focused only on the individual encroachers. Starting from small houses to two-three story buildings, peoples’ homes are being demolished. But these people are individual stakeholders, not organised cartels. Which is why it is very easy to demolish properties using the kinds of drive we now stand witness to as most of these properties were occupied by individuals and were built with the help of local people. In turn, the drives to free rivers of occupancy always seems to overlook areas that are occupied by corporations and landowning cartels. Till date, no such drives have been carried out that could sustain in areas where landowners are set to develop housing projects. These areas are being filled up with soils from rivers. Hence, the authority’s claim that they are carrying out eviction drives sound hollow – it obfuscates the main issue, which is corporate encroachment. Corporate encroachment exists and we have not seen any action initiated on rivers that are occupied illegally by a number of well-known entities. If you consider the rivers around Dhaka city, the drives that were so far initiated covered areas starting from Shinnirtek to Ashulia bridge, Dhour to Tongi, Tongi to Termukh. There were no eviction drives in areas across the northern and southern part of this region. This exemplifies that the authorities are not into account corporate encroachment. So, how can they claim that they have initiated eviction drives? There are factories on river banks that load and unload their goods through the riverways. These factories need to take permits from the jetty to carry out such operations. Now, they are trying to evict these factories and at the same time, are giving them jetty permits. This is not sustainable. Why does the BIWTA issue jetty permits if it is not legal? I think, these contradictions need to be resolved first and it is a big concern that puts question mark on any such eviction drive. These factories have to be moved. There are many locations that have been vacated following the High Court’s order. These properties should be demolished and the BIWTA has a very important role to play in it. It is the Bangladesh Water Development Board’s (BWDB) biggest responsibility, and they are, unfortunately, the ones behind the ruination of the Turag River. Starting from Shinnirtek to Beribadh, the stretch of 90-300 feet belongs to the BWDB and the factories that have sprung up in this area could not have been constructed without encroaching on BWDB’s property. There are around 40-50 structures, and you can also see connecting roads snaking through the entire region. If you question the BWDB, it will testify that it did not construct any connecting roads in the area. Now, the question remains, if the roads are not legal what is deterring the water development board from shutting down factories? The board cannot stop this, they can only operate in the port area. They cannot do anything in the low-lying lands. I would say that the factories in these areas were constructed with the aid of the water development board. Moreover, if the BWDB cut off these illegal connecting roads and bar the jetty permits only then then will these lands be of no interest to the current occupants. If they can accomplish this, they will not even have to take the hassle of demolishing these structures. The occupants will leave eventually. The BWDB has been carrying out eviction drives throughout Bangladesh for the past two days. It has been evicting lowlands in Ramchandrapur of its occupants. The biggest concern is not Ramchandrapur, this government agency should begin taking initiatives to cut off the connecting roads around occupied lands in Ashulia embankment. According to the information provided by the water development board, there are 2200 illegal occupants who have occupied lands that belong to board. Ramchandrapur’s eviction drive is just a pseudo-drive, a hoax, since at first they should initiate eviction drives in and around the embankment. In sum, one may say that the BWDB has played a crucial role behind the illegal occupation of lands around Dhaka. In fact, they have made it easier for occupants to take over. Also, the BIWTA’s demonstration of eviction drive will ultimately not be sustainable if they do not stop authorising jetty permits. The Institute of Water Modelling already did a study on how they can develop the rivers around Dhaka by constructing beautiful walkways on the banks, which also include tourism spots. We have to rescue our rivers, evict occupied areas and then we can think of sustaining the ecology.

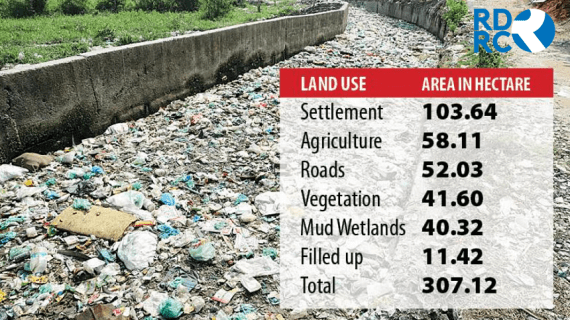

120km Dhaka canals lost to urban greed

Dhaka city has lost a combined length of 120km or 307 hectares of canals, which could have been waterways and vital drainage, thanks to encroachment, unplanned urbanization and lack of maintenance by the authorities in the last 80 years.